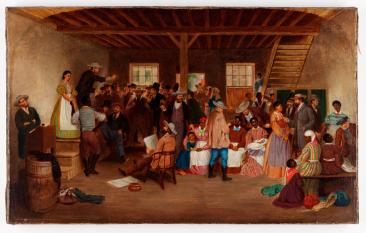

Slave Auction, Virginia, by LeFevre Cranstone, c. 1860s

Slave Auction, Virginia, by LeFevre Cranstone, c. 1860s

Slave Auction, Virginia, by LeFevre Cranstone, c. 1860s

Introduction | Historical Context | Archival Context | The Painting | Activities | Suggested Reading | Standards of Learning

Introduction

LeFevre J. Cranstone, an English artist, created the painting Slave Auction, Virginia in 1862. Cranstone's rendering of the interior world of the auction house highlights the commercial base upon which the institution rested. People were bought and sold like property. A slave was chattel, a word defined in law as "a movable article of personal property, any article of tangible property other than land and buildings; a slave."

LeFevre J. Cranstone, an English artist, created the painting Slave Auction, Virginia in 1862. Cranstone's rendering of the interior world of the auction house highlights the commercial base upon which the institution rested. People were bought and sold like property. A slave was chattel, a word defined in law as "a movable article of personal property, any article of tangible property other than land and buildings; a slave."

Another artist who painted scenes of a similar style and theme was Eyre Crowe. His paintings, Slaves Going South After Being Sold At Richmond and The Sale of Slaves at Richmond, Virginia, in 1853, are examples of the kinds of public art that were being exhibited in England at the time.

Historical Context

The first known Africans arrived in Virginia in 1619. Although little is known of their status, some were probably treated as indentured servants and freed after a period of five to seven years. The institution of slavery was formalized over a short period of time. In 1662, the House of Burgesses legislated that a child's status—free or slave—was determined by the status of the mother. Although this was not the first act concerning slavery as an institution, the 1662 law placed enslaved women at America's economic foundation. By 1700, at least 20 percent of Virginia's population was enslaved. The newly arrived African was typically a child or youth between twelve and twenty-one years of age. Distributed singly or in groups of two or three among small scale planters, most of them proved to be adept both at learning English and mastering chores around the plantation.

At the time of this painting in 1862, America was at war over the issue of slavery. Slave auctions, however, continued, and in Virginia's capital the trade was brisk. At the second largest slave trading market in the South, African American families were frequently torn apart. Cranstone's rendering, though well executed, does not convey the grittiness of the auction houses. In keeping with conventions of the time, his dispassionate artistry had to be made suitable for genteel English audiences in a museum setting.

Archival Context

Slave Auction, Virginia, went on sale at Sotheby's in London in 1990. Prior to that time the painting was in a private collection. In 1991, the Board of Trustees at the Virginia Historical Society approved the purchase of the item, using funds provided by Mr. and Mrs. Robert Jeffress. The director of the Virginia Historical Society and the assistant director of the museum department made arrangements with a dealer in fine art of the American South to bring the painting across the Atlantic.

Before being put on display in The Story of Virginia, an American Experience, the Virginia Historical Society's permanent exhibition, Slave Auction, Virginia was exhibited by The Society of British Artists, in London, in 1863. It was also on display in the exhibit Before Freedom Came, at the Museum of the Confederacy in Richmond, Virginia, from July to December 1991.

The Painting

Oil on canvas, 11 3/4 x 19 1/2 inches. Original frame. Inscribed and signed on stretcher: "Slave Auction" Virginia/Painted by I. Cranstone Hemel Hempstead Hert.

Activities: Guided the Analysis

- Have your students look at the painting closely. What do they notice about the building? What kind of building is it?

- Have your students identify the individuals in the painting. Who is the man standing on the riser, and what is he doing? Who is the man standing at the podium, and what is he doing? Who is the man seated in the chair, and what is he doing? Who is the man holding the woman on the auction block? How many people are in the building?

- Have your students look closely at the people. From their clothing, can you tell anything about the class or status of the whites present?

- Can you see the expressions on the faces of any of the enslaved African Americans? What might this suggest?

- How many enslaved men are in the picture? In the context of the next question, why do you think the painter chose to depict so many enslaved women? Enslaved children?

- In guiding analysis of primary sources, some teachers have students consider the acronym "SPAM" (Speaker, Purpose, Audience, and Message). In this instance, how might the audience (English society women), shape the message?

Suggest Reading

- Campbell, Edward D. C., Jr., with Kym S. Rice, editors. Before Freedom Came: African American Life In the Antebellum South.

- Eltis, David. The Rise of African Slavery in the New World.

- Finkelman, Paul. Slavery and the Founders: Race and Liberty in the Age of Jefferson.

- King, Wilma. Stolen Childhood: Slave Youth in Nineteenth-Century America.

- Schwartz, Maria Jenkins. Birthing a Slave: Motherhood and Medicine in the Antebellum South.

- ________. Born in Bondage: Growing Up Enslaved in the Antebellum South.

- Stevenson, Brenda E. Life in Black and White: Family and Community in the Slave South.

- Wilkins, Roger. Jefferson's Pillow: The Founding Fathers and the Dilemma of Black Patriotism.

Standards of Learning

- VS. 7a

- USI. 8d

- USI. 9a

- VUS. 6c