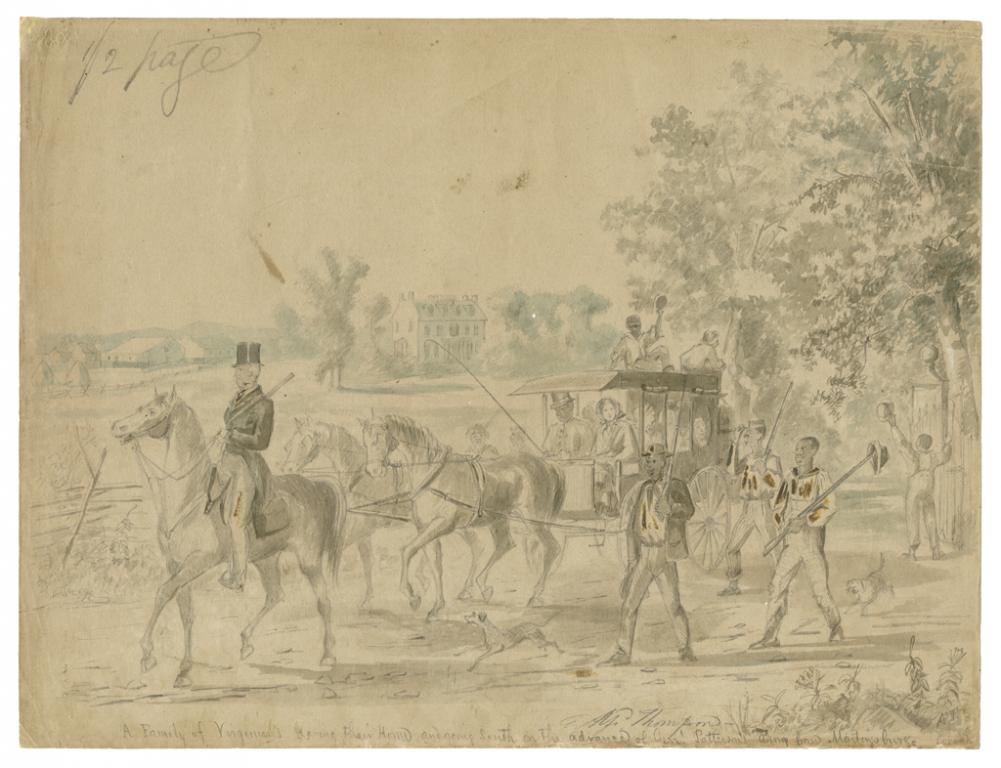

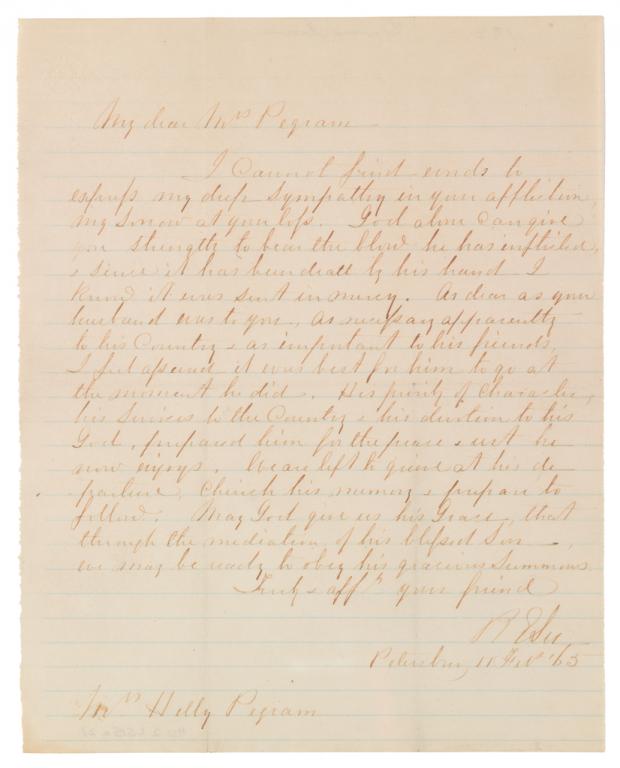

White women and children were left to fend for themselves, and many became widows and orphans when one in five Confederate soldiers died.

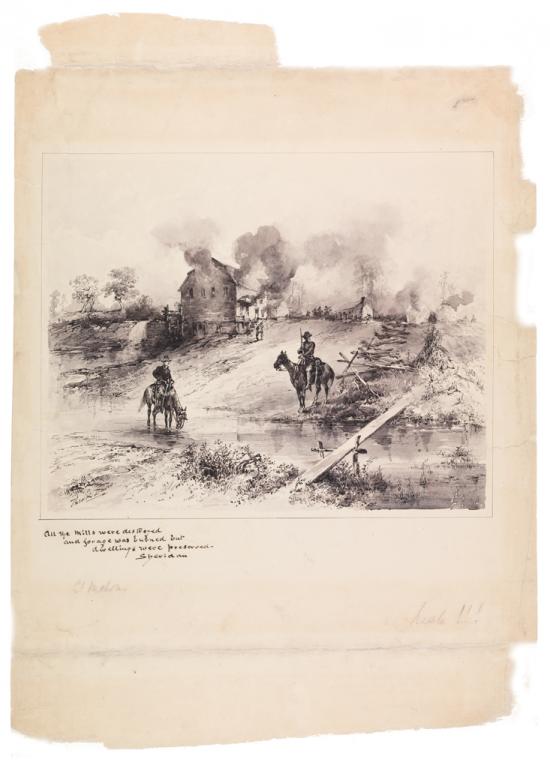

In the countryside, armies destroyed and appropriated property, seized food, burned fences, and turned houses into hospitals. Governments, schools, and churches in their path were closed.

In Confederate-controlled cities, overcrowding, shortages, inflation, and hunger plagued everyone. Residents of northern Virginia, the Eastern Shore, and Norfolk were subjected to curfews, confiscation of property, and sometimes exile by occupying Union forces. The western counties suffered pitiless guerrilla warfare.

Free and enslaved African Americans were separated from their families to labor for the army. Free blacks saw their freedom further restricted as white southerners questioned their loyalty to the Confederacy. Some of the enslaved were removed far from Union lines to prevent their escape. Some families of those who did escape were abused.