School Busing

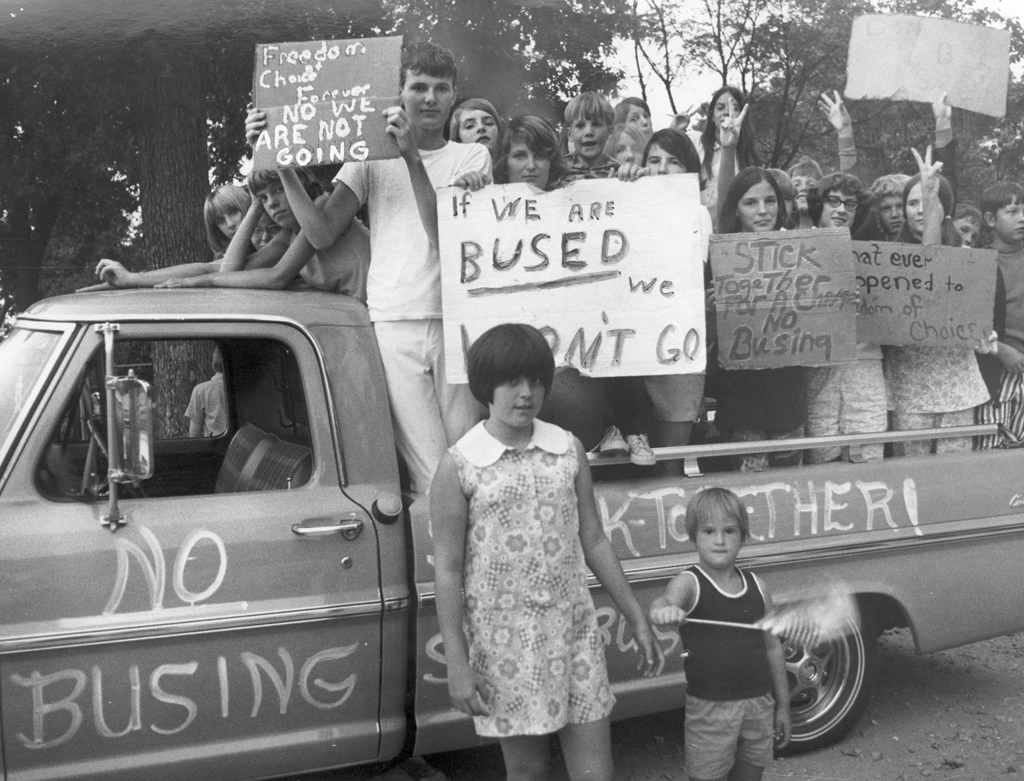

Because Black and white Virginians generally lived in segregated neighborhoods in the mid-twentieth century, race-neutral measures would not ensure racial balance in many schools, which was the new test of legitimacy under the Green decision of 1968. Therefore, race-conscious measures were taken. Supporters called them goals; opponents labeled them quotas.

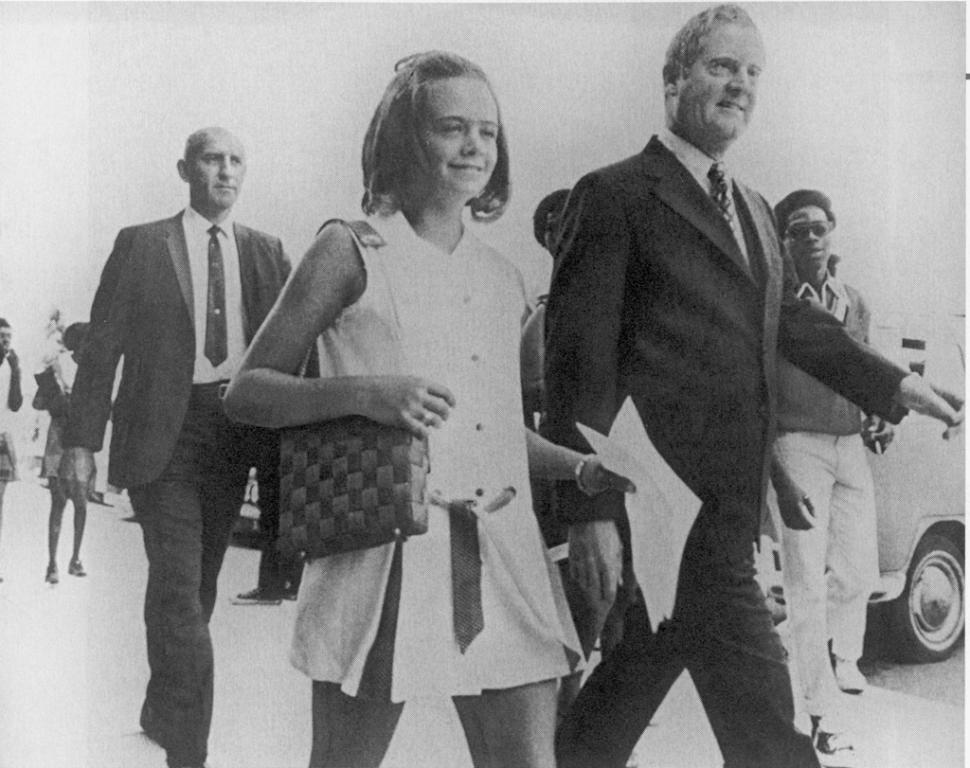

(Richmond Times Dispatch)

In 1970, in the case Bradley v. Richmond School Board, Federal District Judge Robert Merhige, Jr., ordered a limited citywide busing program in Richmond. The decision invigorated white flight to private schools and to the suburbs. Calling it the "only remedy promising success," in January 1972 Merhige sought to nullify white flight by extending the busing program to the suburban counties, so that white children from the counties would be bused into the city and Black children from the city would be sent into the counties. Opposition from white parents was fierce—and soon was felt by politicians. Except in predominantly black districts, few candidates for office in Virginia could be elected unless they vehemently opposed busing.

On June 6, 1972, Merhige's decision was overturned by a 5 to 1 decision of the U.S. Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals. This ruling was affirmed a year later when the U.S. Supreme Court issued a 4 to 4 split decision, as Justice Lewis F. Powell, Jr., former chairman of the Richmond School board, recused himself. The Supreme Court subsequently invalidated most busing across city-county boundaries. As white flight continued in Virginia, Black students again became an overwhelming majority in city schools. This disparity became known as de facto ("in fact") segregation rather than de jure ("by law") segregation because it happened in spite of rather than because of the law.