Fanciful Figures

For most of the 1600s and 1700s, few images of Virginia Indians are known to have been created. Lacking firsthand documentation, European publishers often used illustrations that were imagined by artists. For these representations, which tend to the exotic, the artists borrowed indiscriminately, mixing invented and actual details and interchanging characteristics of native groups from both American continents and from Africa.

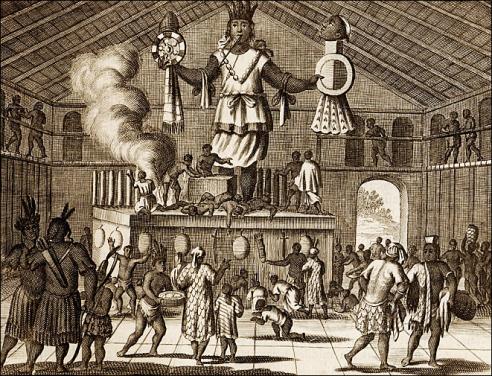

In 1671 the Amsterdam printer Jacob Meurs published De nieuwe en onbekende weereld; of Beschryving van america en't zuid-land, or America, by Arnoldus Montanus, a compilation in Dutch of historical accounts from North and South America. Montanus was a Jesuit and apparently sought illustrations that emphasized the non-Christian, heathen character of Native American religion. To that end, the unnamed artist for the book invented a Virginia scene that borrowed from images of Mexican Indian practice. This concocted scene was in turn copied by other artists.

Other representations of Virginia Indians appear to have been influenced by the notion of the "Noble Savage." Usually identified with Jean-Jacques Rousseau in the mid-1700s, the Noble Savage emerged from the notion that pre-civilized societies were naturally harmonious. Scholarly opinion is that the concept actually originated before Rousseau, with Aphra Behn's Oroonoko of 1688 or Jean de Ury's 1578 account of Brazil.

"Virginien"

"Virginien"

Engraving from book page

From Arnoldus Montanus, America, 1671

To represent a scene of religious practice in Virginia, the unnamed artist for Montanus's America found an icon in a 1622 Spanish book about Mexico, Descripcion de las Indias Occidentales, by Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas. The artist then transformed the Mexican icon into a large idol and placed it in a room modeled on a Mexican temple. The scene falsely presented native Virginia as a cultural province of Mexico.

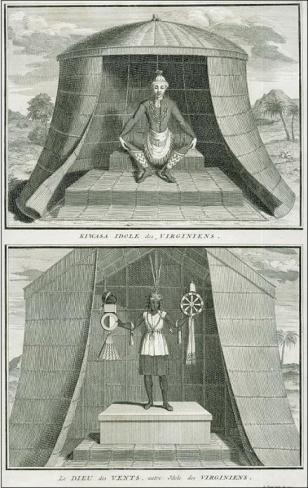

Kiwasa Idol of Virginia, and God of the Wind, or Idol of Virginia

Kiwasa Idol of Virginia, and God of the Wind, or Idol of Virginia

By Bernard Picart

Engraved book page, 1721

Bernard Picart, Ceremonies et coutumes religieuses de tous les peuples du monde représentées par des figures, avec des explications (Amsterdam, 1723–43; later editions 1810, 1819)

Fifty years after the publication of Arnoldus Montanus's America, Bernard Picart produced an illustrated survey of religious practices around the world. For the natives of Virginia, Picart mostly copied from de Bry's engravings, including the Kiwasa Idol here, but for his "Le Dieu des Vents" he borrowed the counterfeit idol image from Montanus's America.

You can see the counterfeit idol in the "Virginien" engraving above.

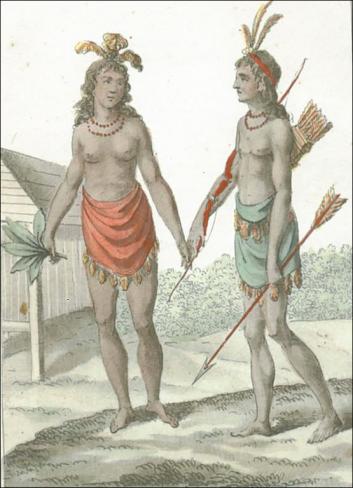

Indian man and woman

Indian man and woman

Engraving, French, c. 1700s

This regal couple appear more likely to have inhabited the European stage than Virginia. Their garments are fabric and instead of tattoos and painted marks they wear necklaces, bracelets, and anklets. The phrase on the banner "Ples de Virginie" is probably "P[eup]les de Virginie," or "people of Virginia"; although "Ples" could also be an abbreviation of "p[er]les," or "pearls," a meaning also suggested by the image.

Homme et Femme de Virginie

Homme et Femme de Virginie

By T. G. St. Sauveur

Hand-colored mezzotint engraving, 1806

Several details in the image appear Virginian in origin, such as the bow and arrow, the bead necklaces, and the loincloths (though they have tassels instead of a fringe). The headdresses might be vaguely based on Virginia imagery, but the milled-lumber house is unmistakably European. The two figures touch hands and gaze at each other. The man holds an oversized arrow that is perhaps less a weapon than a symbol, while the woman holds suggestively-shaped leaves.