Aftermath

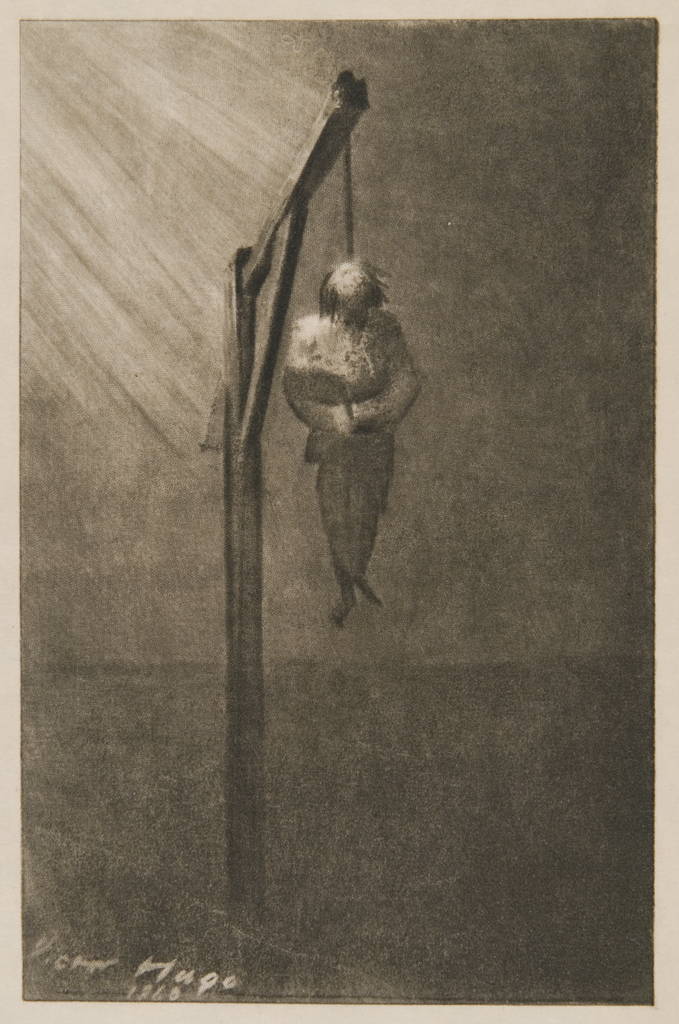

"From the political point of view, the murder of John Brown . . . would impart to the Union a creeping fissure that at the last would rend it." -Victor Hugo

Most white southerners, angry at so bold a challenge to their sovereignty and honor, immediately denounced Brown as a lunatic and criminal. Northern reaction to the raid varied among whites. Many initially rejected his use of violence and were disinterested in his goal. Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and other important New England thinkers, however, took a firm stand in his support from the start. After the hanging, Brown was eulogized by many as a martyr whose death opened the way to emancipation in America.

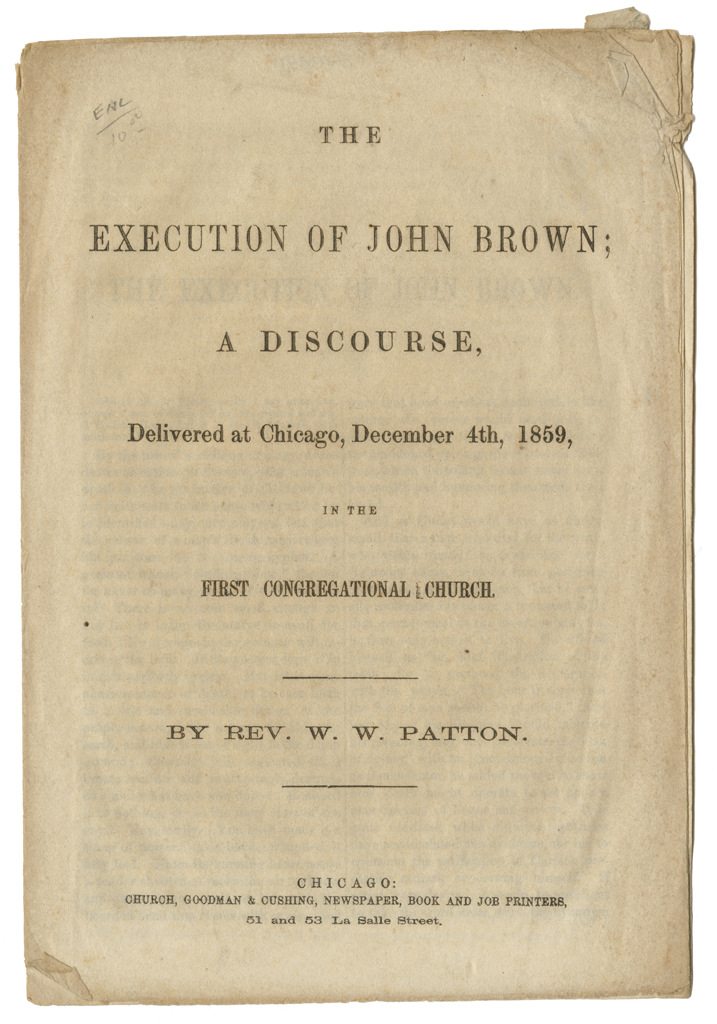

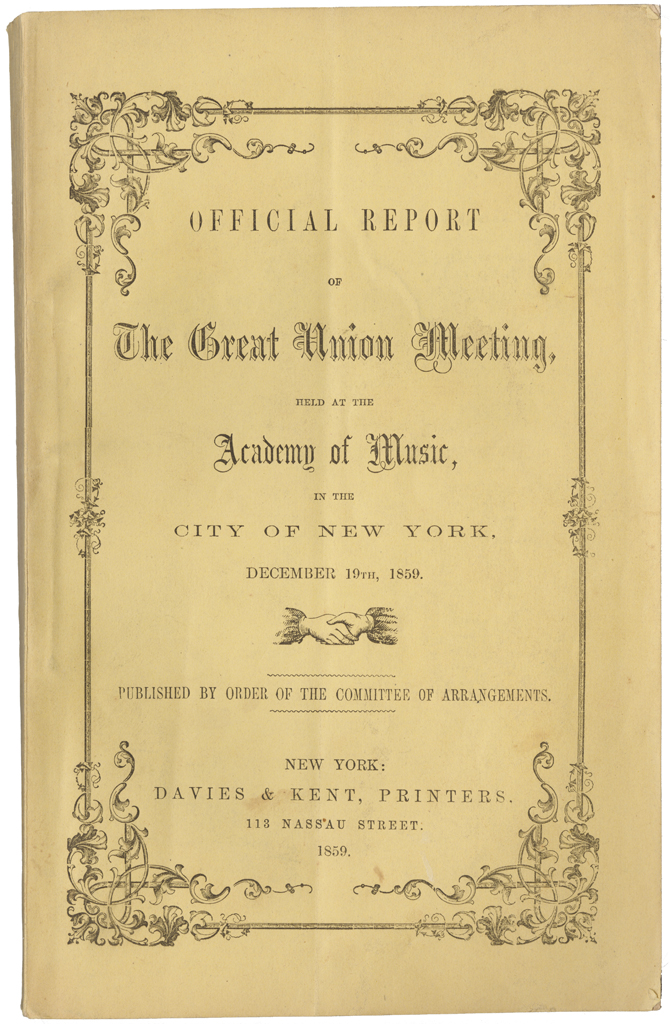

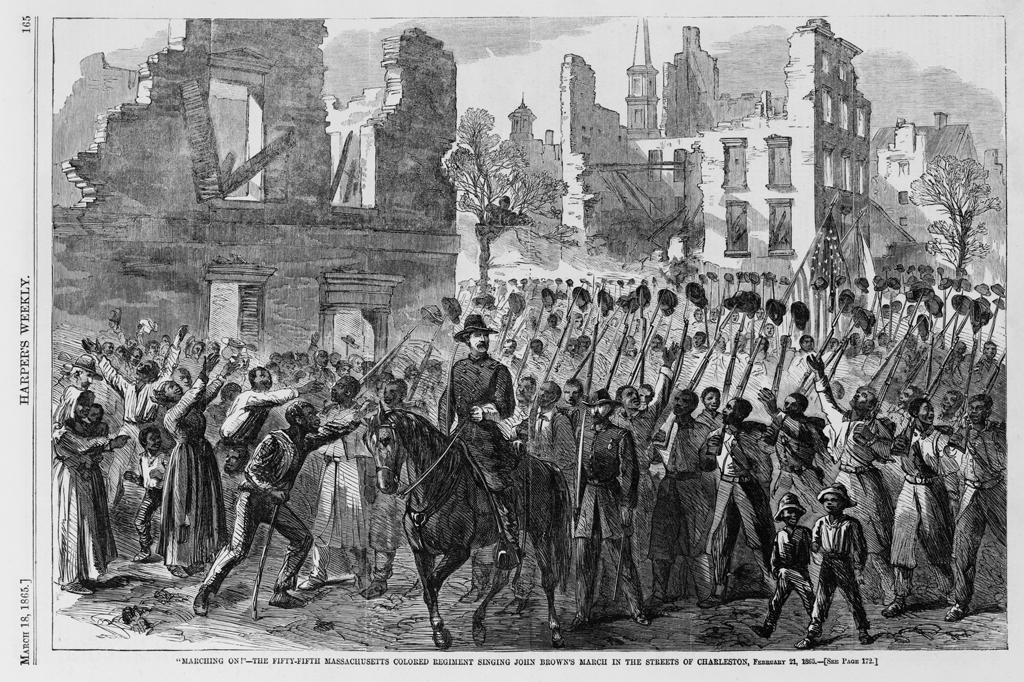

Black Americans, North and South, praised John Brown. Though some denounced his use of violence, at the same time they endorsed his goal of abolishing slavery. Immediately following the execution, meeting halls and churches in the North were filled with sympathizers—white and black—who proclaimed Brown a martyr. These supporters, however, paled in number compared to Brown's northern detractors. Many in the North were content to tolerate slavery, believing it a problem for white southerners alone to resolve. Abolitionist leaders—many of whom had long rejected violence—at least initially denounced Brown's invasion as so great an affront to slaveholders that it would only impede their mission. Leaders of the new Republican Party, which had been founded in 1854 largely to halt the expansion of slavery into the territories, did not advocate abolishing slavery where it already existed and they attempted to distance themselves from Brown. To counter the pro-Brown demonstrations, proslavery businessmen in the North, whose prosperity was linked to trade with the slave-supported economy of the South, rejected Brown outright. They organized massive "Union meetings" in Philadelphia, Boston, and New York City that attracted thousands who denounced both the man and the raid. Southerners, unfortunately, paid more attention to the abolitionist minority.