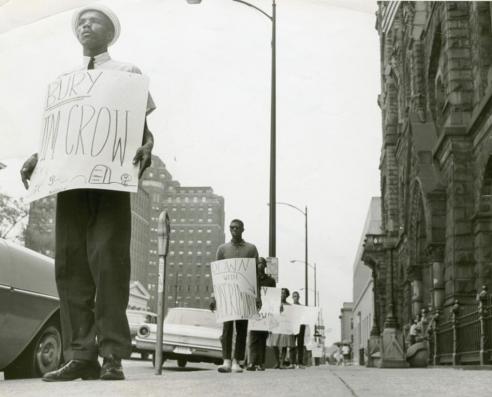

The World of Jim Crow

After the Civil War, Black Americans were no longer enslaved but they had not achieved equal status with whites in American society. The Civil Rights Acts of 1866 and 1875, and the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments to the U.S. Constitution, were made virtual dead letters by hostile court decisions, culminating in 1896 with the Supreme Court’s Plessy v. Ferguson, which gave legal sanction to the principle of "separate but equal" facilities segregated by race.

In fact, separate facilities for black people rarely were equal. They were inferior because segregation—the separation of people based on skin color—was based on the idea, expressed in the Supreme Court's Dred Scott v. Sandford decision of 1857, that "negroes" were "an inferior and subordinate class of beings." Despite the Civil War and emancipation, this remained the attitude of most whites; segregation became commonplace—and was codified by white-dominated legislatures. “Jim Crow,” a name taken from a fictional minstrel character, came to be the nickname for America's own system of racial apartheid.

In Virginia, the South, and some northern states, Plessy v. Ferguson both confirmed the status quo and gave impetus to even more rigid segregation laws. Black passengers were forced to sit at the back of streetcars or stand if there were not enough seats for whites. They were made to sit at separate sections of theaters, libraries, and train stations. People of color could not use water fountains, bathrooms, beaches or swimming pools used by whites. They could only order takeout food from restaurants that served whites. Black children attended separate, usually ramshackle schools. Social activities, along with everything from sports teams to funeral parlors, were segregated. When Black people donated blood, it was segregated from that of white donors.

When Black members of the military traveled—in uniform—they often were not allowed to use restrooms at bus terminals and gas stations, and instead were directed to a nearby tree. After Korean War-veteran Thomas Hardy returned home to Virginia, in 1951, he wondered "What was I fighting for?"