Jefferson was a member of America’s early artistic generation, which included the painters John Singleton Copley, Benjamin West, and Charles Willson Peale, all born in the 1740s. He was creative, teaching himself architecture by studying (mostly out-of-date) European pattern books, which convinced him that ancients Greeks and Romans had developed a perfect architecture based on the right proportions, or the unchanging "Laws of Nature." Then Jefferson moved beyond the books and tradition. He innovated, introducing octagons and the dome to American architecture, taking from contemporary France the flowing space and convenience of rooms on a single floor, stretching out long decks and walkways along shallow rooms (at Monticello and the University of Virginia), and incorporating his love of natural scenery by providing views from windows and doors and by building his house in the sky—all to achieve the “light and airy effect” that he described to friends as the goal.

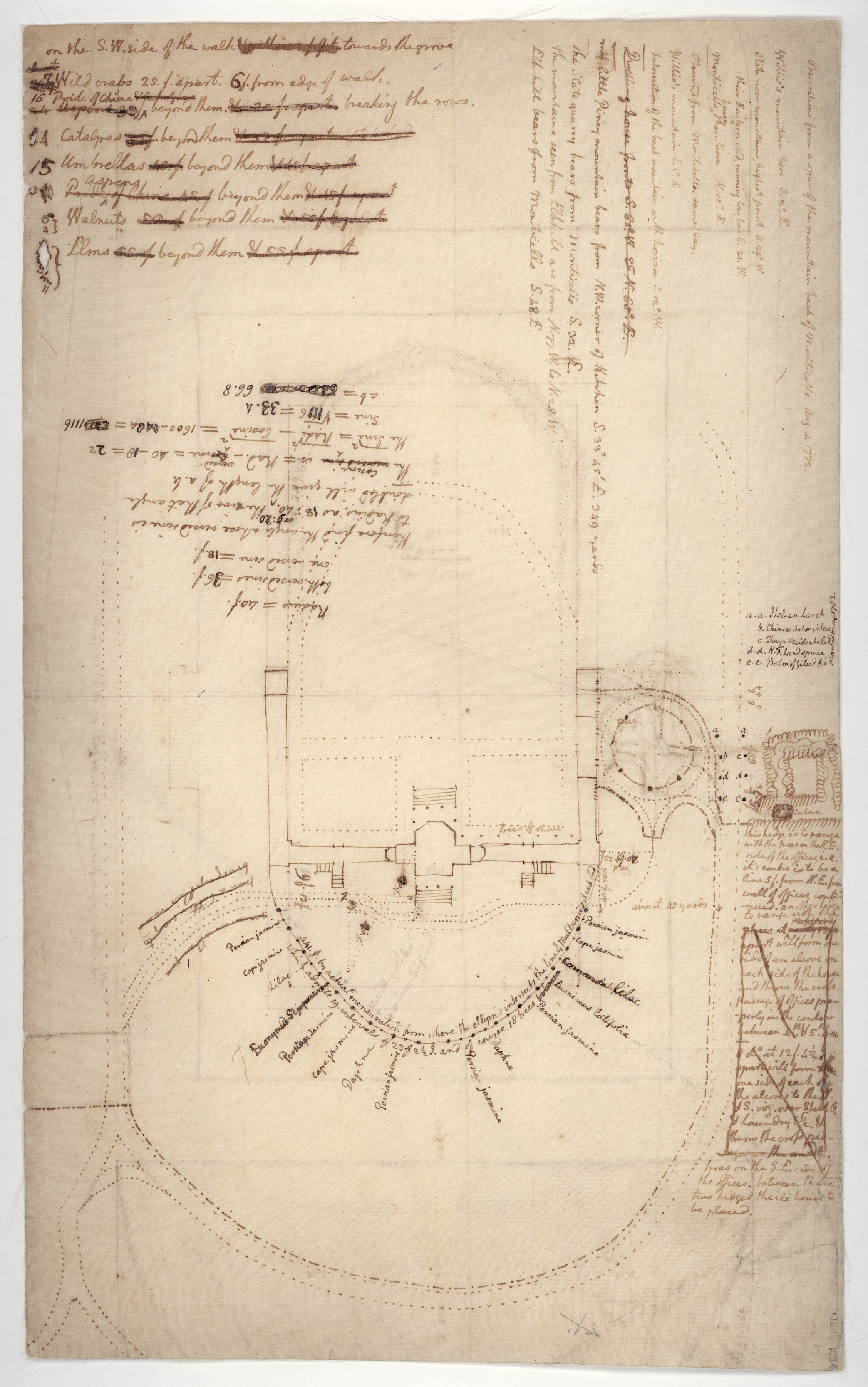

Jefferson ranked his introduction to America of olive trees and upland rice from Italy as among his major contributions to the nation. He argued, “The greatest service which can be rendered any country is to add [a] useful plant to its culture.” Jefferson the gardener stated, “No occupation is so delightful to me as the culture of the earth.” He built a 1,000-foot terrace into the side of the Monticello mountain so he could experiment there with vegetables and herbs—with 330 varieties of 99 species. He introduced 125 varieties of fruit trees. Having toured gardens in England with John Adams in the 1780s, Jefferson designed pavilions to serve as focal points for his gardens at Monticello (they were never built). Among the extensive farm records he kept are tables of crop rotations and lists of harvest times. Gardening and farming are wholesome, he concluded, writing “I think our governments will remain virtuous for many centuries as long as they are chiefly agricultural.”

This article was adapted from one written by William M. S. Rasmussen in conjunction with the exhibition, The Private Jefferson, while he was serving as lead curator and Lora M. Robins curator at the Virginia Museum of History & Culture. The Private Jefferson: From the Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society was on view at the VMHC in 2016. Want to learn more about Thomas Jefferson? Check out this blog that William Rasmussen contributed to the Virginia Repertory Theatre.